Money for nothing

Or for not much... or so it seems. Why the investigative due-diligence is not something you want to skip.

It is a bad day for the university administrator. With state funding for higher education shrinking all over the developed world, universities now spend more and more time looking for private donors. It can be a thankless task, especially when donor candidates don’t work out. Such is the case at the fictional Pelican University, inspired by real events. Names have been changed to protect the unscrupulous.

(And it doesn’t have to be a university administrator, either: it can be the budget officer for a beleaguered local-government authority, or the board of an up-and-coming start-up trying to secure its next round of financing, or really any institution in need of private financing or investment. In this case, it just happened to be a university.)

Just as the weary administrator is about to give up for the day, her inbox chimes. The email is from an outfit she has never heard of before, the Jones Foundation, which despite the name doesn’t come from Wales but from Boreania, a significant emerging market. The email comes from the personal assistant to Mr. Jones himself, who is presumably the chairman of the foundation. Mr. Jones is apparently a successful property entrepreneur who would be honoured to have the opportunity of a meeting to discuss potential endowments to the university, says the assistant. Would that be possible?

The administrator barely hesitates. Here is a good way of turning a particularly bad day, coming at the end of a particularly bad few months, on its head. A few follow-up and scheduling emails later and Mr. Jones’s plane touches down at the nearest international airport. He arrives at the university with his staff. He is well-dressed, but modest and soft-spoken. Through an interpreter, he claims to have come from humble peasant stock, making his fortune through trade in South America – his wife is Peruvian, he says – and later being fortunate enough in his own country to be able to grow his earnings through successful property investments. Brochures are duly deployed. Luckily, he and his family now no longer want for anything, he says, and he has conquered all he wants to conquer in business. He is growing old and tired, and feels a sense of duty towards the world. What he really wants to do is play his own modest part in developing a department of Boreanian Studies at a receptive university. His country is still too little known, he feels, and the victim of too much prejudice. He wants to make it his legacy to correct this, so that more foreign investors are encouraged to come to his country and offer opportunities to the young in his country, and which he himself never had. Halfway through a sumptuous lunch at a nearby Boreanian restaurant, the university officers nod gravely: what a noble aspiration. They part with Mr. Jones with broad smiles and uplifted spirits: Mr. Jones has hinted at a gift in the millions of dollars, and perhaps even more. This would go a long way towards filling the university’s donor target, and would also put the university on the map as a leading research centre for Boreanian Studies, a strategic area in which it lagged behind its competitors until then. Mr. Jones doesn’t even insist on personal recognition, and assures the university they would have complete freedom in their choice of staff and research subjects, although of course he would be delighted to advise if his counsel were needed. There seems little not to like.

The administrator would dearly like to feel as enthused as her colleagues, but she feels unease that so little is verifiably known about Mr. Jones. She raises these objections with her colleagues, but is told, in effect, not to be a killjoy: who knows what the “typical” background of businessmen-philanthropists from Boreania looks like anyway? And if this opportunity is passed up, what are the chances of another one remotely like it in the foreseeable future? The administrator sees their point, but she still ends up contacting a specialist investigative due-diligence firm, who quotes a reasonable price for looking into the detailed background of Mr. Jones. The administrator pleads with her colleagues to allow an investigative due-diligence to be carried out. But her colleagues overrule her, irritated by what they see as an inexplicable eagerness to look a gift horse in the mouth. Mr. Jones is delighted. His endowment goes ahead.

A year later, a long article appears about Mr. Jones in the Investment Times, the premier business publication in the country. It makes for disturbing reading.

First of all, according to the journalist who did the deep-dive into Mr. Jones, Mr. Jones is not Mr. Jones: as often happens in his country, he had adopted an alias to distance himself from his achievements. He is really called Mr. Kleen (the headlines write themselves). Unlike what he had claimed, he had never set foot in South America, either, and his wife was not Peruvian but Boreanian, like him. Far from being the salt-of-the-earth farmer he claimed to be, Mr. Kleen was the son of a senior army officer who used his father’s army connections to secure a plum posting as a border guard which availed him of lucrative smuggling opportunities. Mr. Kleen and a group of similarly minded acolytes thus made fortunes from smuggled jewellery, some of it confiscated from border-crossers looking to infringe capital controls. Instead of handing over the confiscated merchandise to their government, Mr. Kleen and his accomplices kept it for themselves.

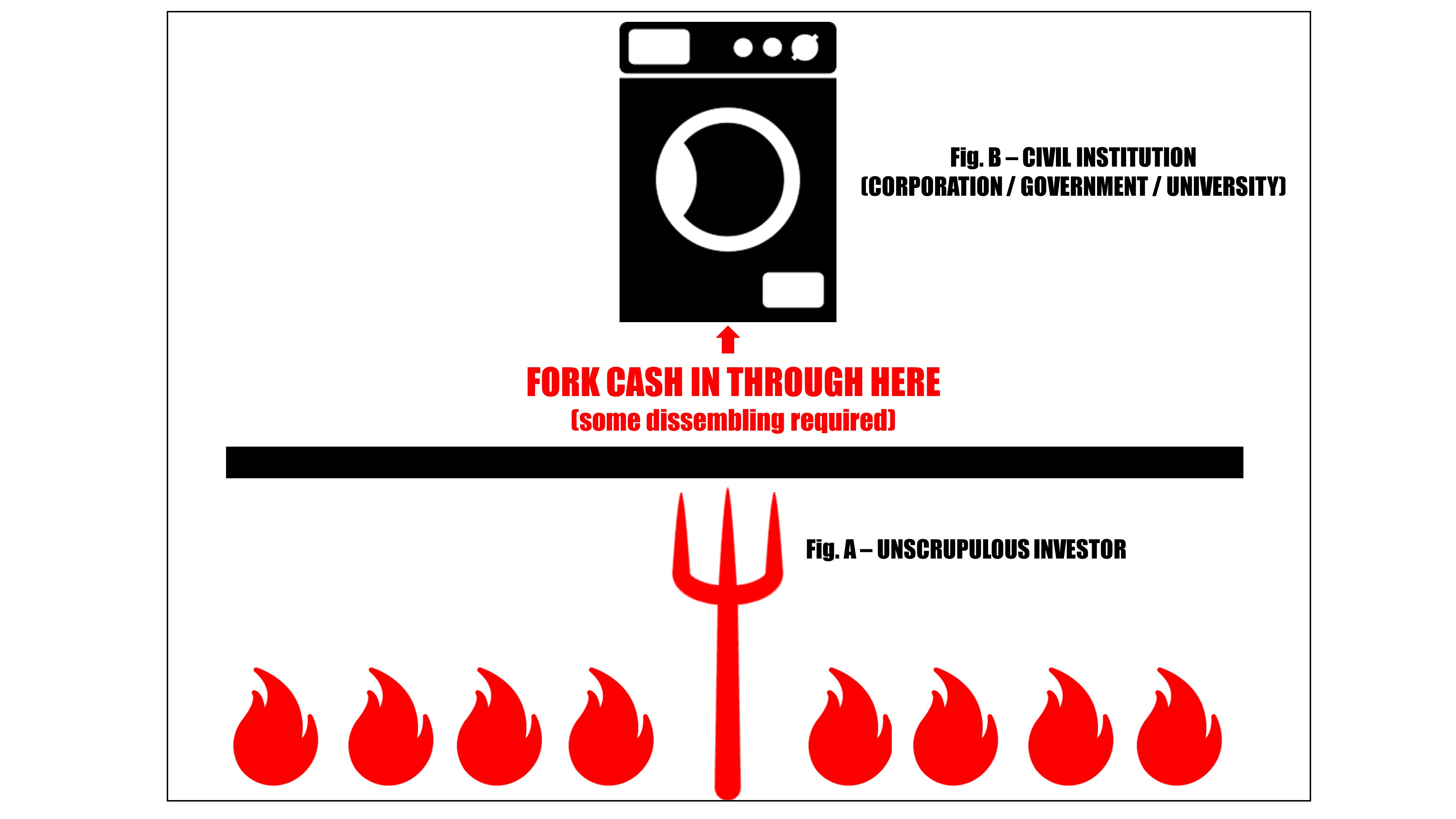

After over a decade of this plundering, all the gold was becoming inconvenient to hoard, and Mr. Kleen and his friends looked for a way to launder their proceeds and maximise their returns. Luckily, Boreania’s government at the time was busy liberalising property ownership, and Mr. Kleen took advantage of this. Setting up a string of foreign-registered companies which allowed him to present himself to the untrained eyes of his government-employed compatriots as having prestigious outside backing, he used one of these companies to get into a joint-venture to develop a property with a municipal government at the other end of the country. Mr. Kleen let the local government do all the hard financing, and then ran away with the government money injected into the joint-venture, leaving the government to develop the project entirely on its own.

But Mr. Kleen had even loftier ambitions, and duly set off for Blingville, the capital of Boreania, burgeoning at the time after decades of relative isolation from the outside world. Using his newly acquired money, Mr. Kleen set about bribing the land-management officer in Bonanza, one of the city’s up-and-coming districts, who obliged by defrauding local residents of their housing and granting Mr. Kleen a parcel of prime real-estate right under the noses of genuine and established real-estate developers.

Mr. Kleen then repeated the trick in an even more promising district, incorporating a property management company in which he appointed the local land management officer as chairman, setting him up to make a large part of the proceeds from subsequent property development. The grateful land officer set about evicting the residents and flattening their houses, with those residents who petitioned the government against their expropriation ending up harassed and detained. In the meantime, Mr. Kleen subcontracted the actual development of the property to a government company to avoid digging into his own pockets or actually having to develop the site himself, and just sat on the property to let it appreciate and make a killing on its eventual sale. The government company subcontracted by Mr. Kleen turned out not to have the qualifications to develop the site, so it set up a market on the site and charged rent to local stall-owners (almost all of whom made their living from illicit knock-offs of famous brands). The rent from these stall-owners, in majority funded from product piracy, was handed over to Mr. Kleen. The site was eventually sold for a hundred million dollars, most of which of course also went into Mr. Kleen’s pockets.

Meanwhile, since Mr. Kleen did not, of course, know how to develop property, he was not able to finish the property in the first Blingville district where he had settled, Bonanza. He colluded with corrupt municipal-government officials to set up property joint-ventures which allowed these rapacious officials to become overnight property tycoons by dipping into Blingville’s pension fund: the corrupt officials would collaborate with Mr. Kleen in acquiring and supposedly developing prime real-estate with embezzled pension-fund money. One of these sites was the Bonanza project itself, which received tens of millions of dollars from the Blingville pension fund, yet somehow never managed to get off the ground despite having been widely advertised as one of the city’s most prestigious venues. Embarrassed, the municipal government injected even more money into Mr. Kleen’s Bonanza project to get it finished on the condition that he repay this money from tenancy fees after completion. The project was finally finished, but the city never saw any of its money. Instead, Mr. Kleen’s company became the largest creditor of one of Boreania’s top banks, with debts in the hundreds of millions.

Mr. Kleen then changed his name, and started giving money to charity and other places that might take his cash, for example putting tens of millions of dollars into the tiny kingdom of Bobo, whose banking transparency rules made some of the more enterprising Caribbean territories look like paragons of virtue by comparison. Thus it was that one fine day, Mr. Kleen had happened to knock at Pelican University’s door, as the Investment Times journalist revealed, and was welcomed with open arms.

When contacted by the journalist, the university, caught entirely by surprise, could only plead ignorance. By that stage, the university’s new centre for Boreanian Studies had already been up and running for a while, and a former finance minister with a hitherto pristine reputation – and who had also not bothered to hire a due-diligence firm to look into the funding of the centre – had been made its chancellor. The university suffered a severe blow, and became the target of student protestors. Placards reading “Pelicans Standing With Vultures” appeared. The hashtag “#PelicansOrFatCats” started trending on Twitter. Other donors pulled funding. The education minister promised an inquiry.

But it didn’t stop there. Because of who the chancellor was, the scandal also rocked the government. Questions began to be asked about who knew what, and when. This precipitated an early election.

If only the diligent administrator had been listened to.

© 2016-2019 Code 19 Business Intelligence Limited – All rights reserved.